Local economic innovation is taking place in the UK’s cities, but you won’t find it where you might expect it. It’s there in a run-down building full of makers on the edge of an empty ‘enterprise’ zone. It’s on the 1960s estate in Wolverhampton where a group of young people are setting up a digital factory. It’s in the traditional boat-building enterprise giving older men hope and human connection in the former-ship building area of Glasgow.

While government has spent millions developing economic plans, enticing big business into areas and creating innovation parks and enterprise zones, a different kind of local economics – one that starts with people and the places they live in – has been slowly coalescing.

Its roots are in places left behind by the mainstream economic model, those so-called ‘doughnuts of deprivation’ that ring our city centres but which never feature in their tourist brochures. With little private sector investment and at the sharp end of public sector austerity, these places have quietly been finding their own solutions, building housing, creating jobs and livelihood and hope.

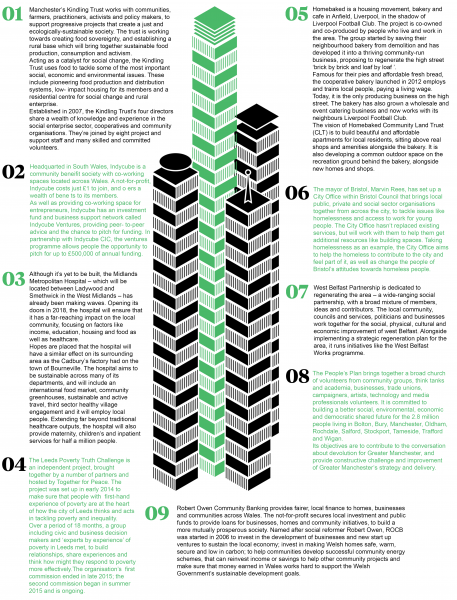

Some – like Liverpool’s Granby Four Streets – have hit the headlines, winning the Turner Prize in 2015 and putting community economic development into the spotlight. But most of them, from the network of co-working spaces across the South Wales valleys to the social enterprise making furniture in Bristol’s Knowle West, are working under the radar, hand-holding, experimenting, seeing what will work.

They are often precariously funded and sometimes they fail. But as the problems of the mainstream economic model have become more widely exposed, and as we face up to the profound social, technological and environmental challenges we are living through, these local economic experiments look like a way forward, combining social, economic, and environmental aims, working with the buildings and people that are already there and building upwards.

Last year New Start, together with the Centre for Local Economic Strategies and the New Economics Foundation travelled the UK visiting ten major cities and finding examples of this approach.

We began by calling it an ‘alternative’ approach to local economics but quickly realised that the projects we found were by no means radical.

Community land trusts, co-working spaces and social supply chains are building a new approach to local wealth and prosperity. They are focused on good sustainable employment and affordable housing, stimulating enterprise and ensuring public and private sector wealth is distributed more evenly.

These local economic models and structures may not fit with the current mainstream approach, but they work. They are happening ‘at the pace of imagination’ and challenging the traditional structures within places, which are mostly struggling to keep up.

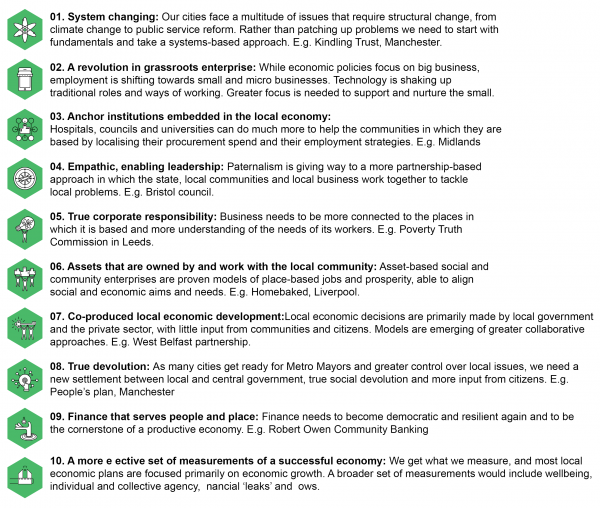

The culmination of our research was a report called Creating Good City Economies in the UK, in which we set out ten steps to a good city economy.

At a time when local economic policy is still stuck in the 1980s, these principles are an approach to local economics more suited to the challenges of the 21st century.

What if we turned the current economic model on its head and instead of pouring money into city centres and technology parks and waiting for it to trickle down to poorer areas, we started in those areas with the assets already there and worked upwards? What if the burgeoning network of community land trusts spread to every town and city? What if a percentage of the money currently spent luring big business into cities was instead directed at grassroots enterprise and experimentation?

Since the vote for Brexit the clamour for a new social and economic model has got louder. As part of the Good City Economic project we are now working with five UK cities to put good city economy principles into practice, embedding social and grassroots approaches into mainstream economic plans, bringing the ‘big’ together with the small and focusing on the foundational economy.

When innovation is taking place on housing estates rather than innovation parks and when enterprise flows from a bakery rather than an ‘enterprise’ zone, it’s time to re-assess our local economic aims and priorities.

Clare Goff is the editor of New Start Magazine.

To follow the Good City Economy work join us: www.newstartmag.co.uk